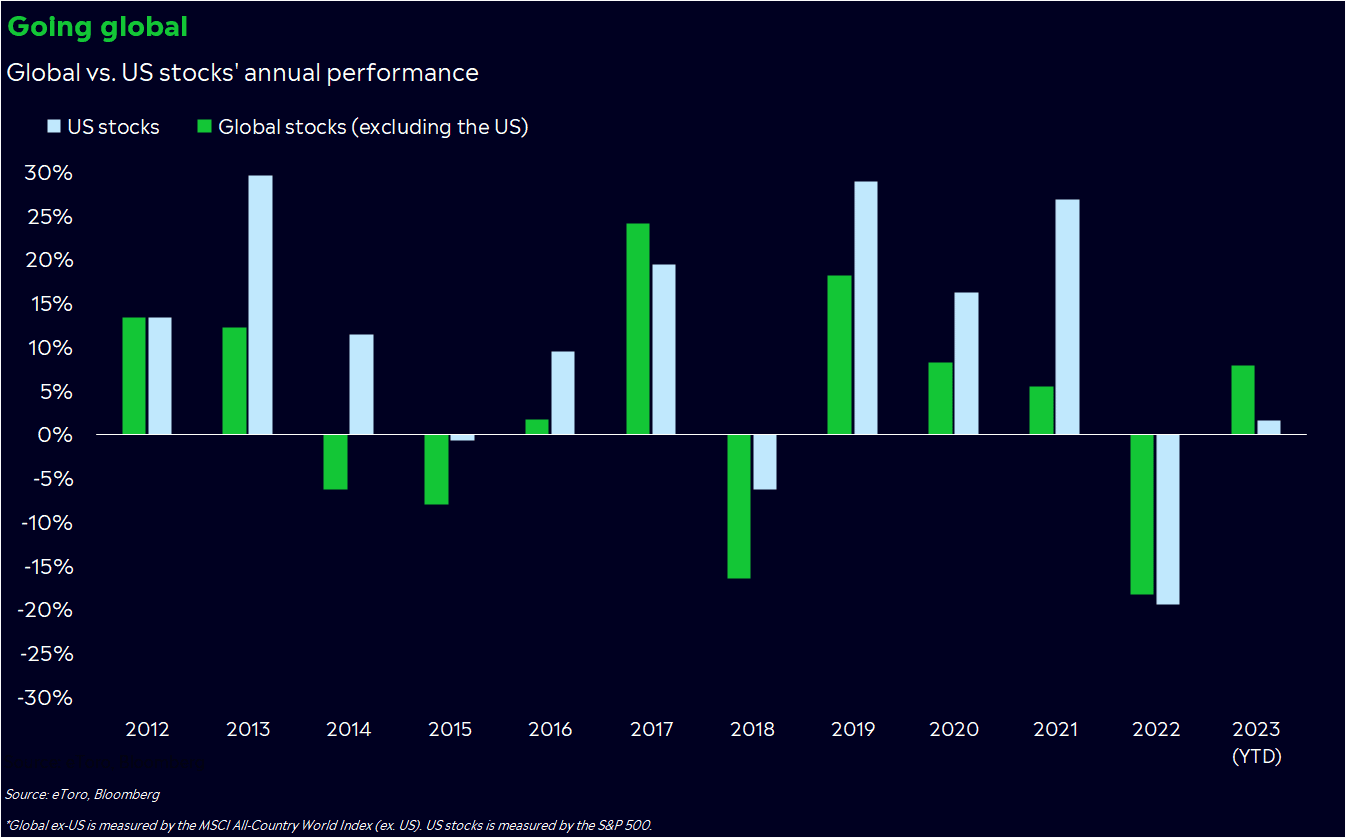

Global stocks — or markets outside of the US — are having their best start to a year in at least three decades, and they’re trouncing US stocks.

It’s a rare feat for the rest of the world, which has trailed the US market in eight out of the last 10 years. The American home bias that’s dominated over the past decade may be disappearing right before our eyes.

It’s not necessarily because the path may be better for the global economy than the US. It just may be less bad.

But for investors trudging through an environment of scarce opportunity, that seems to be good enough.

International developments

As US investors, we’ve had our hands full with market-moving news. Slowing (but still high) inflation, lower demand, fourth-quarter earnings, Jay Powell’s COVID case — should I go on?

It’s easy to get distracted with all the noise, but developments overseas have been just as interesting over the past few weeks. Europe has delivered a surprisingly strong slate of economic reports, and both currencies and commodities have started to turn in the global economy’s favor.

Then, China started to shed policies that have kept its economy locked down for the past three years. That’s a big deal: China is the world’s second largest economy and more than 20% of its manufacturing capacity, so its welcome back present could provide a noticeable boost to growth while easing some trade and supply chain headaches.

China is also one of Europe’s big trade partners, so China’s grand re-opening could help ease the oil and gas shortages Europeans are dealing with. Markets are already starting to ease up, with natural gas prices dropping 65% in five months. It’s also worth remembering that Europe’s inflation is largely goods-driven, with food and energy making up about half of the rise in prices over the past year. China’s small steps could go a long way.

And we can’t talk about global progress without mentioning the US dollar. The dollar’s meteoric rise last year caused a rush into dollar-denominated assets and made US goods more expensive to foreign consumers. The pressure has cooled since September, though, as the dollar has dropped 11% versus other currencies.

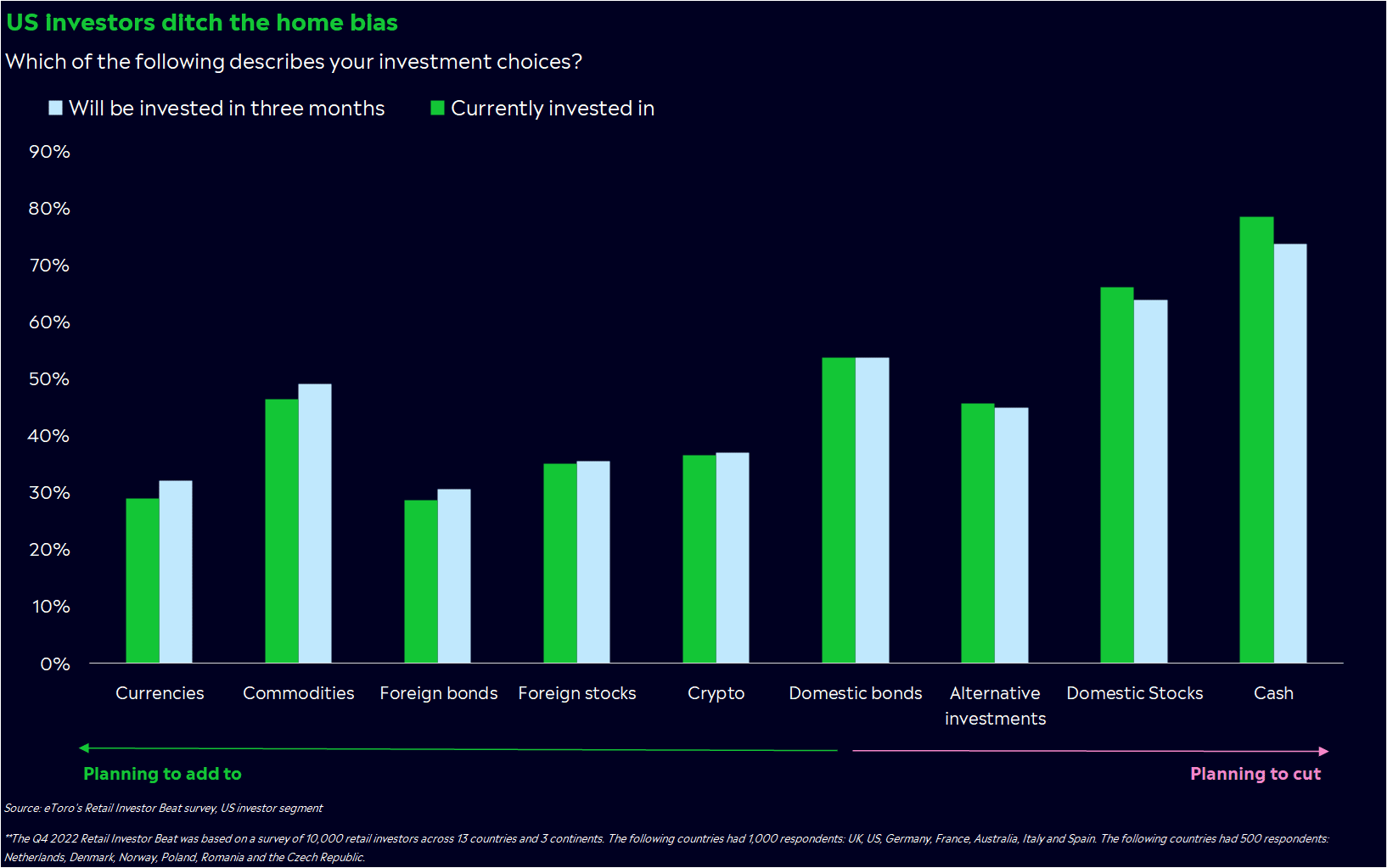

Now, both individual investors and Wall Street are ditching their US investments for overseas opportunities. Retail investors are planning to pivot more into foreign stocks and bonds over the next three months, according to our fourth-quarter Retail Investor Beat survey (which included 1,000 investors). 24% of US investors said a potential US recession is the biggest external risk to their portfolios, compared to 16% who cited a potential global recession as a key risk. Money managers are holding the least amount of US stocks relative to their benchmarks since 2005, as they’re moving into European and emerging-market stocks, according to a Bank of America survey.

Growth or value?

The investing world may be turning its back on the US, and there are a lot of reasons to think the global economy won’t go through another year as dismal as 2022.

But is the grass really greener on the other side of the pond? It may just be a little less yellow and muddy than we thought. Not great, but less bad.

To understand what I mean, it’s worth taking stock of where the global economy stands. We’ve talked a lot about the US economy: resilient, but showing cracks. Europe is still strained for growth and trying to tackle 9% inflation. China is reopening, yet there are worries that flipping the switch back on could unleash another bout of inflation. Persistently high inflation — no matter the source — could keep central banks in hiking mode for at least the next few months.

There aren’t any clean shirts, but then again, we know we’re digging through a dirty laundry pile. All the shirts have stains. The difference may be in which one has the fewest stains, or how attractive each region’s stock prices are relative to the others. Maybe people are turning to international stocks because they look like a good bargain versus their US counterparts?

A good way to measure value is through price to earnings ratios, or what price an index is trading at relative to the earnings its companies are generating. And if you look at the S&P 500’s price-earnings ratio relative to other regions, you can see a new story emerging. Even after a nasty bear market, the S&P 500’s price-earnings ratio is around 17 (if you base it on forward earnings estimates). That’s about the average for the past 10 years – during zero interest rates and an economic expansion.

In contrast, Europe’s and China’s price-earnings ratios (judged by the Stoxx 600 and the Shanghai Composite Index) are significantly below their 10-year averages. In fact, at 13 (for Europe) and 11 (for China) both price-earnings ratios are near 10-year lows. In other words, it looks like international stocks are trading at a deep discount, while US stocks are just on sale.

This is what I mean by not great, but less bad. Growth overseas may not be gangbusters for a year or two, but in an environment where value is scrutinized and dollars are stretched, international markets may be the more enticing option.

Traveling abroad

Investors’ fascination with international markets may be from a mix of hope and bargain hunting. It’s wise to think beyond your borders, especially when the US may be facing a rough year. But while the global economy seems to be on the upswing, there are still plenty of risks to consider.

Before you travel abroad in your portfolio, evaluate how sensitive the US side of your portfolio is to changes in the global economy. Many sectors, like tech, industrials, and healthcare, generate a portion of their sales internationally. An improving global economy could be a good thing for these sectors, but it’s important to understand your exposure before adding more.

*Data sourced through Bloomberg. Can be made available upon request.

**The Q4 2022 Retail Investor Beat was based on a survey of 10,000 retail investors across 13 countries and 3 continents. The following countries had 1,000 respondents: UK, US, Germany, France, Australia, Italy and Spain. The following countries had 500 respondents: Netherlands, Denmark, Norway, Poland, Romania and the Czech Republic.