The balance of power in the job market has tipped from employers to employees.

Lately, that power has manifested in a series of strikes — from Hollywood writers to delivery drivers and baristas. So far, the strikes have caused minor, annoying inconveniences, like longer shipping times, delayed flights, and shorter TV seasons.

But now, we may have to deal with strikes — or shutdowns — in two economically critical sectors: autos and the government.

A major wall

Last Friday, 13,000 workers in the United Automobile Workers union — one of the largest unions in America — went on strike against Ford, GM, and Stellantis. And as you’re reading this, the UAW strike may be growing, since union leaders set a September 22 deadline for negotiations before another round of factory strikes. If all 146,000 of UAW’s GM, Ford, and Stellantis members join the picket line, it would be the biggest single strike since 1998.

If that’s not enough disruption, politicians are haggling over the federal government’s budget. If no budget is passed by October 1, parts of the government could be shut down. Thousands of non-essential government employees could go without pay until Congress agrees on a budget.

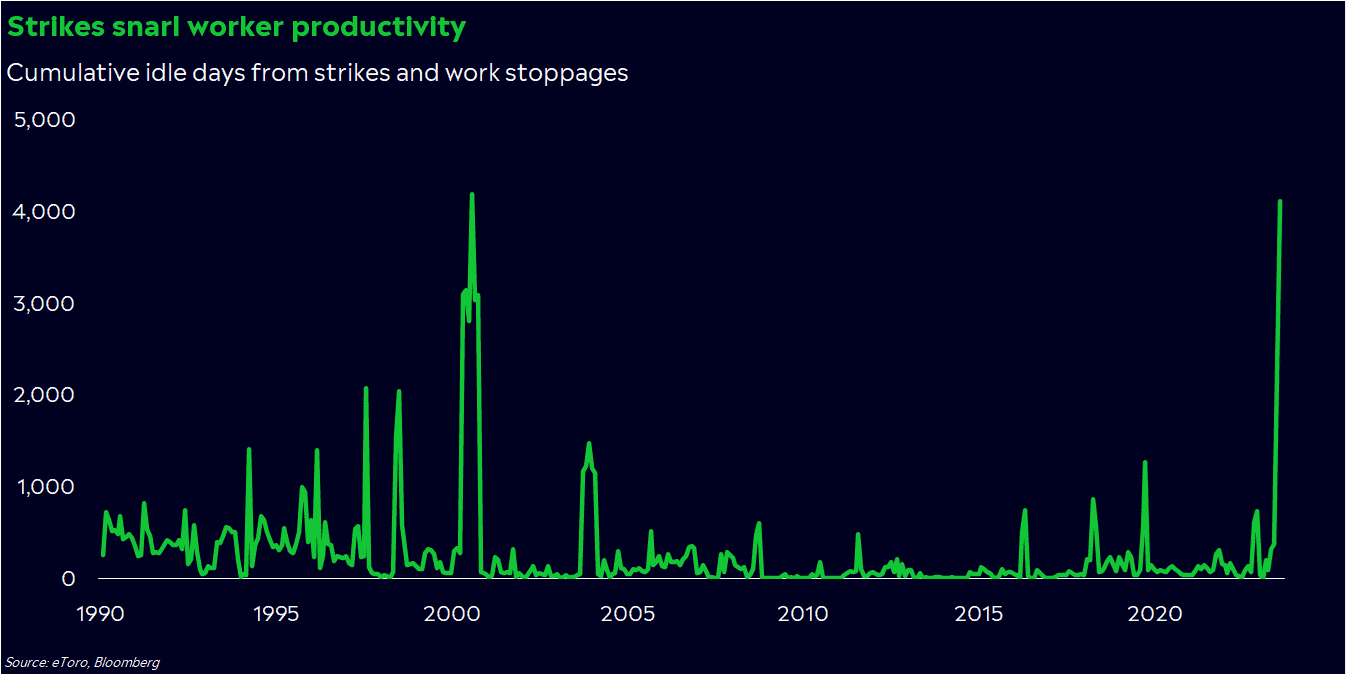

Add that to the myriad of strikes going on right now, and the economy could hit a major wall. In August, strikes and other work stoppages led to the most idle days among workers in two decades. A bigger UAW strike and potential government shutdown could make a bad situation a lot worse.

Now, let me be clear. Employees should have a voice in their working conditions, especially after a decade of companies focusing more on profits than worker pay. This is a crisis, and it could lead to lots of long-term economic and social problems — like a growing wealth gap and shrinking productivity.

Still, we need to talk about all the economic — and market — consequences that come along with major shocks like strikes and shutdowns, especially in today’s fragile environment.

Auto supply and demand

If you’re like the average American, you spend a lot of time in your car. 11 hours per week, according to some estimates.

Just like you and your car, the US economy is heavily dependent on the health of the auto industry. About one-fourth of US manufacturing and one-fifth of retail sales come from car production and sales. In this context, the UAW strike could theoretically cause enough disruption to slow down the economy.

But will that actually happen? It all depends on supply and demand.

The auto industry has been dysfunctional these past few years — and that’s putting it lightly. Supply chain issues have weighed on inventories, which are down to about a third of what they were pre-COVID.

And on the buyer’s end, soaring car prices and loan rates have made it less appealing to buy a car, so slowing car production may not matter as much if the demand isn’t there. It’s also important to remember that the US accounts for 20% of the world’s vehicle sales, even though America made just 3% of cars produced worldwide last year. Global production is much more important in the grand scheme of things.

Of course, all this matters more if you’re an auto stock investor — or somebody in the market for a new car. Automaker profits could come under pressure if sales slow and wages increase.

But remember — UAW isn’t the only strike going on right now. Several industries are feeling the pressure from picket lines, and other unions are on the verge of strike. And the government holds a similar importance in people’s minds. The government may not be a tradeable industry, but a widely-telegraphed political squabble can have a chilling effect on the economy.

The impact on economic data

A less obvious risk could be how the strikes and shutdowns show up in economic data. Markets are especially focused on data these days, and who can blame them? The economy’s health seems to be the million-dollar question on Wall Street, and the Federal Reserve constantly reminds us how data-dependent their rate decisions are.

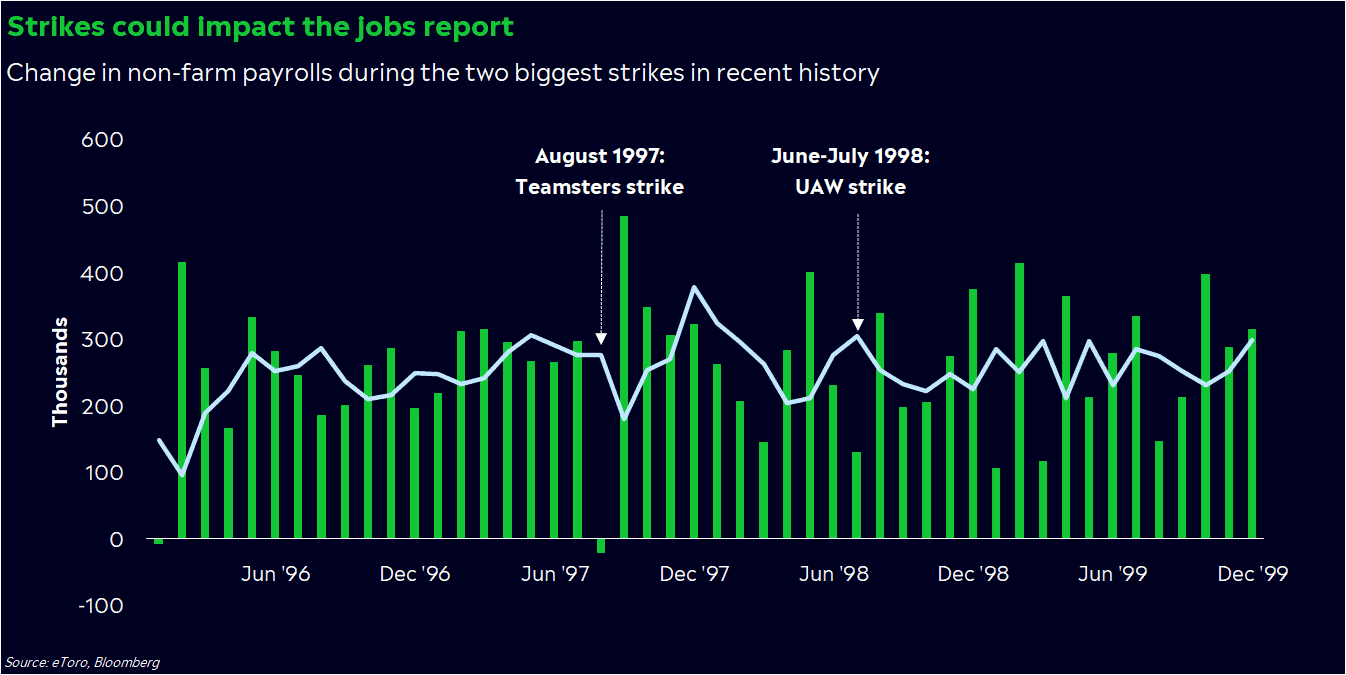

Unfortunately, the data could start getting weird. Manufacturing reports (ISM data, industrial production, durable goods) may be heavily affected by any drop in auto production from the UAW strike. And the jobs report — one of the most widely watched economic releases these days — could be especially tainted.

In the past, the Bureau of Labor Statistics has subtracted furloughed and striking workers from payrolls. It’s a temporary tweak, but one that could be drastic enough to throw investors off. The two biggest strikes in recent history (the Teamsters strike of 1997 and the UAW strike of 1998) led to payrolls prints that were at least 170,000 jobs below the three-month hiring trend.

Bloomberg Economics even estimates that a month-long UAW strike could cause payrolls to drop in October — a trend we typically see around recessions. The jobs report and other releases may even be skipped in the event of a shutdown.

Of course, this has implications for the Fed’s quest against inflation. If the Fed can’t get a clear message on where the economy is going, they may not feel bold enough to make any policy decisions. And if the Fed feels left in the dark about the economy, imagine how the average American feels. We’ve seen consumer confidence drop noticeably in past shutdowns, and strikes can lead to more friction in our everyday lives. So don’t be shocked if a prolonged season of strikes and shutdowns dulls confidence and weighs on the stock market.

So what does this mean for me?

Check your stocks. Strikes and shutdowns could hit the entire market, but you should care even more if you hold auto, industrial, or defense stocks. Those industries may be more impacted.

Think beyond the system. Strikes and shutdowns are two clear signs that the traditional system isn’t working for certain groups of people. Think about how decentralized alternatives like crypto could respond to a prolonged phase of disruption.

See the bigger picture. I’ll leave you with some good news:. Obstacles like these rarely last longer than a few weeks. Since 1990, government shutdowns have lasted an average of two weeks, and strikes have taken about a month. Yes, they can roil markets and cause other problems, but they rarely lead to bear markets or larger crises.

*Data sourced through Bloomberg. Can be made available upon request.