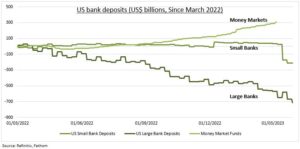

VIEW: The March US banking ‘scare’ may seem to be mostly behind us. But many of the macro consequences remain, and history reminds these can be big and global. The $17.3 trillion of US commercial bank deposits, equal to 65%/GDP, continues to slowly fall. This predated the failure of SVB and is driven by the Fed’s 5% policy rate. Depositors are naturally moving to higher yield money market funds, which are at a record $5.2 trillion. Tighter liquidity is slowing loan growth, doing Fed’s work for it. IMF forecasts show this could cut 0.4% from US and Euro GDP growth. It also presses banks to raise deposit rates, eating into their profit margins. See @BigBanks.

OUTFLOWS: The immediate systemic threat to US banks has been staunched by stepped up Fed liquidity support and targeted full deposit guarantees. Deposit outflows have slowed and emergency Fed lending needs eased. But the steady, though manageable, deposit outflows and switch to higher yielding money market funds pre-dated the SVB failure and is continuing (see chart). This will 1) pressure bank profitability as deposit rates are raised, 2) slow bank lending as liquidity tightens, and 3) be exacerbated by the natural step up in bank regulatory scrutiny.

HISTORY: The history of banking crises is sobering. There have been 151 systemic bank crises around the world from 1970-2017. Some have seen many, like Argentina, Congo, Ukraine. They last longer and are more costly in richer countries, with high bank penetration and debt levels. They are rarely single-country events and often come in waves. The policy response typically starts with liquidity support and bank guarantees, to buy time. This often leads to administrative measures, like worst case ‘deposit freezes’. Followed by costly recapitalization and resolution efforts. Monetary and fiscal policy is quickly loosened to cushion the high macro consequences.

All data, figures & charts are valid as of 12/04/2023