Ready to learn about options? In this article, we’ll walk you through some of the basic terminology and strategies surrounding options.

Call and put options offer ways for traders to speculate on whether they think an asset price will go up or down. The mechanics of these two types of options work in a similar way, and help you to get exposure to a market by putting forward a relatively small initial capital outlay.

Options are a

What are calls?

Calls may be the best-known type of option. They offer the option holder the chance to purchase an underlying asset at a predetermined strike price. If the strike price is lower than the market price when the option expires, that is advantageous for the option holder, but not for the option seller who needs to make delivery of the underlying asset.This means the best time to buy a call option would be when you expect the price of the stock to go up before the expiry date.

Tip: One call option in a stock will give you the right to buy 100 shares.

There are four potential outcomes once you purchase your call option.

- Profit

- Breakeven

- Partial loss

- Total loss

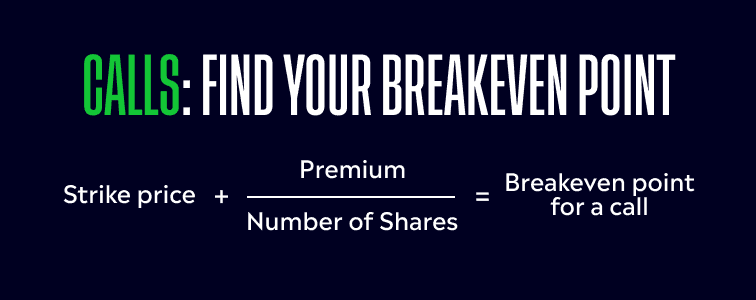

We’ll start with breakeven, since that acts as the baseline for the rest of the outcomes. Essentially, breakeven is the point where the money you put in is the same as the money that comes out. You didn’t make any money, but you also didn’t lose any either — you’re left with net zero on your investment.

A trade’s breakeven point is the strike price plus the option premium. Let’s look at a hypothetical scenario of an option approaching its expiry date:

You buy a call option for 100 shares of your target stock.

Strike price: $10/share

Option cost (premium): $100

The stock price then rises to $11 — past your $10 strike price.

As exciting as the news is, you haven’t quite reached the profit point yet. Why? Because $11 is your breakeven point. You made $100 ($1 for each of your $100 shares), but you spent $100 to buy the option in the first place. That leaves you with net zero.

Of course, it’s rare for a stock to land exactly on your breakeven point at the time your option expires. That leads us to the other three scenarios.

Let’s continue with the most favorable outcome: a profitable trade.

In order to profit on a call option, the price of the underlying stock needs to move above your breakeven point.

For every $1 above the breakeven point the stock moves, in theory, you’d get $1 for every share in profit. If we go back to our previous scenario, that means a move to $12 makes you $100. If it goes up to $15, you’ll make $400. At $21, you’d make $1,000. This demonstrates how small changes in share price can add up to large amounts of value — once you pass that profit point.

But what about the other side? Well, if the stock never reaches your strike price, you lose the whole investment — that’s considered a total loss. But, you can rest easy knowing that in almost all situations, your initial investment is usually the most you’ll lose.

And what about the space between your strike price and your breakeven point? In our previous scenario, that would be the price between $10 and $11 — let’s say it lands on $10.50 at the time of expiry. In this case, you’d experience a partial loss. You made $50, but you originally put in $100 — so you’d still be losing $50 overall. While no trading loss is ever welcome, it compares well to what your losses could have been had you taken a position of 100 shares of the underlying stock.

The terms “in the money” and “out of the money” are used to describe options and profitability. Put simply, “in the money” means that the stock price has surpassed the strike price — meaning that you are in partial loss, breakeven, or profit territory. “Out of the money” means the stock price has not met the strike and on expiry date, the trade will be a total loss.

What are puts?

Puts work on the other end of the spectrum. When you buy a put, you’re reserving the right to sell shares at, hopefully, a higher price than they are trading at (when the option expires).

There are two main times that you might want to buy a put. The first is when you expect the price of the stock to go down. The second would be as a

Just like calls, puts have four outcomes:

- Profit

- Breakeven

- Partial loss

- Total loss

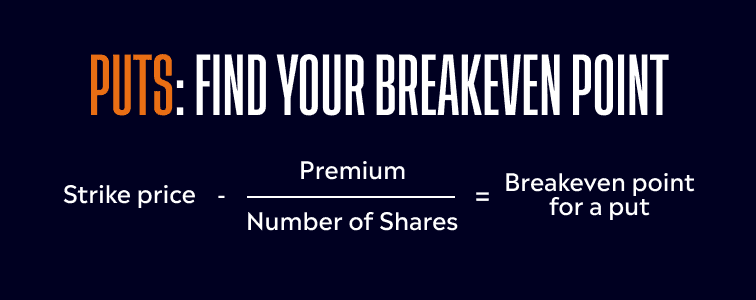

But in this case, the profit begins when the stock goes below your breakeven point, rather than above it.

Let’s go back to our previous example, except this time, you think the stock price is going to drop below $10:

You buy a put option for 100 shares of a stock you think will decline.

Strike price: $10/share

Option cost (premium): $100

Let’s say the stock then drops to $9. You would make $100 ($1 for each of your $100 shares), but you spent $100 on the put in the first place, once again putting you at net zero. Again — not great, not bad, just okay.

Now, let’s say that stock dropped to $8. At this point, you’ve made $200 — minus the original $100 cost — meaning you’ve made $100 profit.

At $7, that grows to $200 of profit. At $1, you’d make $800 in profit. The lower the stock goes, the more money you would make.

That means that between $9 and $10 puts you in the partial loss scenario, and anything above $10 will create a total loss situation. But just like a call, this total loss is (usually) limited to your original investment in the option* — in this case, the $100 premium — because you can simply choose to let the option expire.

Tip: Although rare, there are certain cases in which you may be exposed to greater loss than your initial investment.

For a put, “in the money” and “out of the money” mean the same thing as they do for a call. If you’re “in the money,” the stock has dropped below your strike price (partial loss, breakeven, or profit); if you’re “out of the money” on expiry date, you’ll have a total loss.

Final thoughts

Different options can help you build out your portfolio in different ways, but all of them require some kind of opinion about the market and some hands-on activity. Once you understand how puts and calls work, you can use them to gain exposure to different markets by only putting forward a relatively small amount of capital.

Learn more about ways to use put and call options by visiting the eToro Academy.

Quiz

FAQs

- Can you use calls and puts in the same strategy?

-

There are some strategies which involve simultaneously opening positions in calls and puts. One is a long straddle which involves buying a call and a put option in the same underlying stock with the same strike price and expiry date.

- Can you make greater returns from calls than puts?

-

The upside on a put option trade is capped at the underlying instrument reaching a price of zero. A long position in call options on the other hand generates returns when prices rise, and since there is technically no limit on how high a stock price can go, there is potential for greater returns.

- What is the put-call ratio?

-

The put-call ratio is a calculation that divides the number of traded put options by the number of traded call options. Once you establish the long-term ratio, you can identify if the ratio is currently above or below the long-term average. If the ratio is higher than it typically is, that shows more puts are being bought, which is a bearish sign, and vice versa.

This information is for educational purposes only and should not be taken as investment advice, personal recommendation, or an offer of, or solicitation to, buy or sell any financial instruments.

This material has been prepared without regard to any particular investment objectives or financial situation and has not been prepared in accordance with the legal and regulatory requirements to promote independent research. Not all of the financial instruments and services referred to are offered by eToro and any references to past performance of a financial instrument, index, or a packaged investment product are not, and should not be taken as, a reliable indicator of future results.

eToro makes no representation and assumes no liability as to the accuracy or completeness of the content of this guide. Make sure you understand the risks involved in trading before committing any capital. Never risk more than you are prepared to lose.