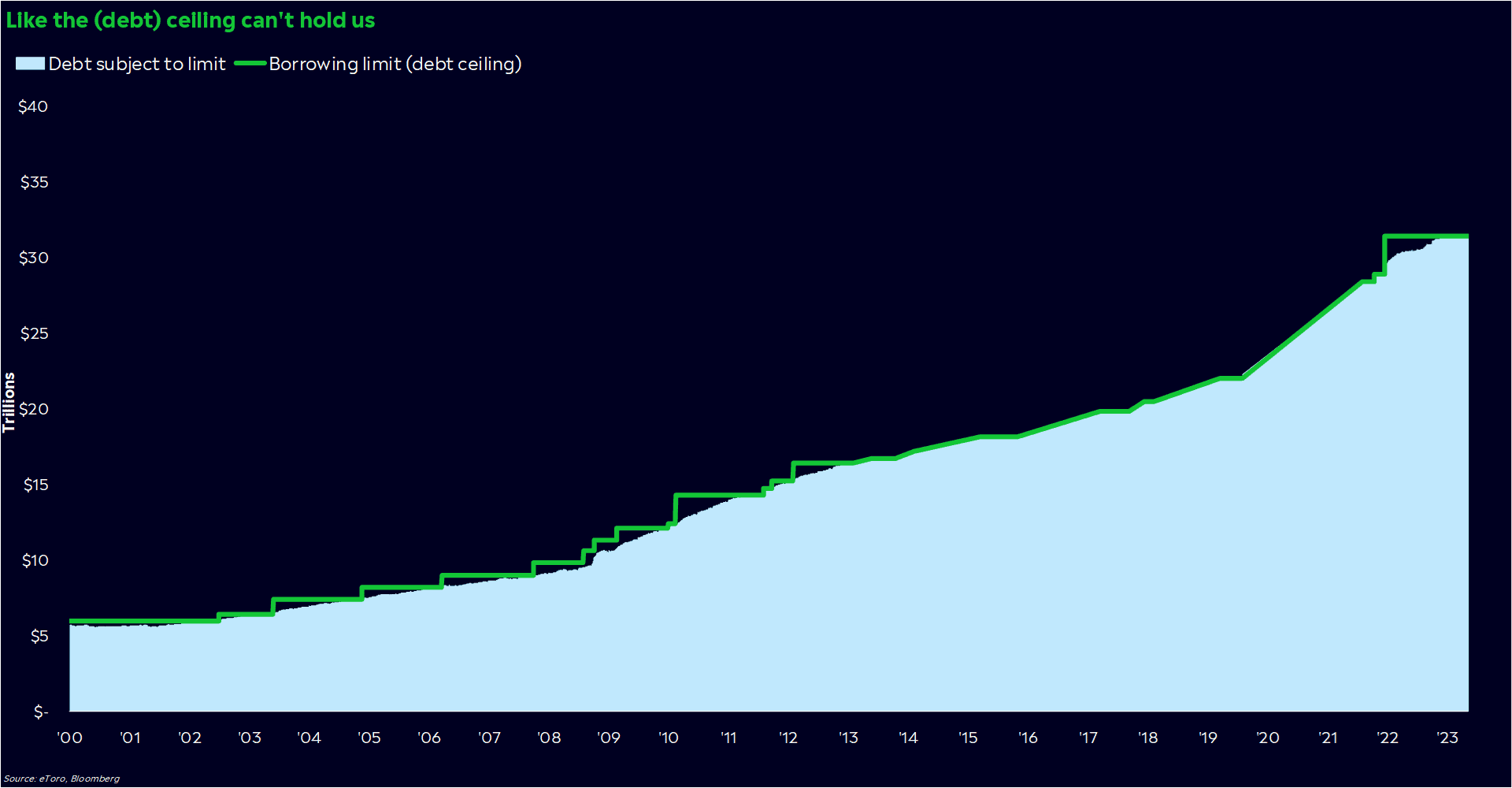

The debt ceiling drama is heating up.

We’re now weeks away from the US potentially defaulting on its debt — an unprecedented event that could cause mass unemployment and business disruption (the White House’s words, not mine). While we’re not there yet — the dreaded, uncertain X date when the US government can’t borrow any more money — we’re inching closer, with little resolution.

It may feel easy to brush off the debt ceiling crisis, especially because nobody can pin the actual X date down. Plus, we’ve all become numb to contentious political headlines.

But this time, the back-and-forth could be worth paying attention to.

Even if we don’t get that dreaded default.

It’s getting real

The debt ceiling drama has been in the news since January, when the federal government first hit the limit in January. The Treasury was able to move money around to buy some time, but Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen warned that the US could potentially default on its debt this summer.

Now, it’s May, and we’re still haggling over the debt ceiling. And after a new round of number-crunching, Wall Street’s policy analysts think the X date could be anywhere from the beginning of June until August. Potentially a matter of weeks, not months — and there are only a handful of days between now and the beginning of June, when President Biden is in DC and Congress is in session. It’s gradually looking like we could be in for a repeat of 2011’s crisis, during which Congress raised the debt ceiling just two days before a potential default.

Things are getting real — and fast. So why aren’t investors flinching?

Well, some of them are. One-month Treasury yields have surged to a record high, and gold prices are up 12% since mid-March. So far, it’s looked like a repeat of 2011: a rush to safety and tangible investments, as the worst-case scenario becomes more of a possibility.

The stock market is eerily quiet, though. The S&P 500 is near 10-month highs, and the VIX — a measure of one-month S&P 500 options — is still below its long-term average of 20. Compare that to 2011, when the S&P 500 dropped 17% in a month and the VIX spiked as high as 48, its highest point outside of a bear market in history.

To be fair, it’s tough to know how to react in an unpredictable scenario like this. These days, investors have iron stomachs, but it’s important to note that 55% of all investors started investing in the last 10 years, according to the US segment of our Q1 2023 Retail Investor Beat survey. They weren’t investing during the 2011 fiasco.

And in this topsy-turvy world of high inflation, debt ceiling stress could actually propel certain stocks higher. Investors have gravitated towards defensive stocks since banking issues popped up in March, and lower long-term yields — like we saw in 2011 — may spark another rush into rate-sensitive sectors. Stock buyers are swooping in quickly these days, too. Could this crisis be another hurdle for the market to jump over?

The consequences of a near-default

There are lots of theories you could point to, but I think the most probable one is pretty straightforward. In many investors’ minds, a default would be so catastrophic that you’d think there’d be enough incentive on both sides to reach a deal. So why worry?

Well, a near-default can come with serious consequences.

We learned as much from 2011. After the debt ceiling crisis died down, the US’ borrowing power was somewhat compromised, and it eventually resulted in implicitly higher loan rates for everyone. Yes, even you and your mortgage. There were other costs, too — the programs that lost funding in the government’s debt limit-forced budget cuts, the time people spent on debt ceiling talks that could’ve been devoted elsewhere, and the investments that were nixed because of political uncertainty.

Congress may avoid a default again, but building tensions could weigh on the economy at a time when it’s under a lot of pressure. A drop in consumer confidence — similar to the plunge we saw in August 2011 — could be enough to impact spending. There may also be spending cuts as part of the debt ceiling negotiations. We tend to forget about government spending as an economic driver, but it’s contributed an average of 0.7 percentage points to GDP growth in the last three quarters.

Most importantly, coming close to the X date could ruin the perception of the US’ creditworthiness, and that could harm the US’ status within the global economy for years to come.

So what does this mean for you?

Evaluate your needs. Are you planning to make moves in your portfolio over the next few weeks? If you answered yes, make an action plan in case markets turn on debt ceiling fears.

Prep your portfolio. You may be in denial or think that you have time on your side. But the time to prepare for a storm isn’t when the rain and winds are beating down on you. Besides, short-term swings can happen at any moment, regardless of the reason. Don’t let them catch you off guard.

Watch the banks. In the 2011 crisis, banks were the hardest hit of all S&P 500 sectors, likely because of their proximity to interest rates. Debt ceiling fears could set off another round of worries for banks, and financial system cracks can spread quickly.

Think about the long-term consequences. As time goes on without a deal, the chances of long-term repercussions grow. Treasury yields could move higher, and government spending plans could evaporate — leaving a hole in funding for important things like infrastructure and clean energy.

Remember the alternatives. There’s already palpable distrust within the traditional financial system, so imagine what a near-default of government debt could do. To be clear, we don’t think the US economy is doomed. But this could be another argument for the use of decentralized finance as a compliment to the system we already use.

*Data sourced through Bloomberg. Can be made available upon request.

**The Q1 2023 Retail Investor Beat was based on a survey of 10,000 retail investors across 13 countries and 3 continents. The following countries had 1,000 respondents: UK, US, Germany, France, Australia, Italy and Spain. The following countries had 500 respondents: Netherlands, Denmark, Norway, Poland, Romania and the Czech Republic.