We’ve been stuck in this inflation crisis for what feels like forever.

And now, the latest worry on Wall Street is that higher-than-average inflation could stick around for much longer. Investors in the bond market are already preparing for this reality, and a few well-known experts — like Oaktree’s Howard Marks and PIMCO legend Mohamed El-Erian— have even warned that the Fed may have to be satisfied with 3 to 4% inflation versus the 2% they’re aiming for.

You may find it silly to be arguing over a percentage point of price growth per year. And yes, in that context, it does sound trivial.

But modestly higher inflation may be more than just a number — it could be one of the biggest risks to your finances.

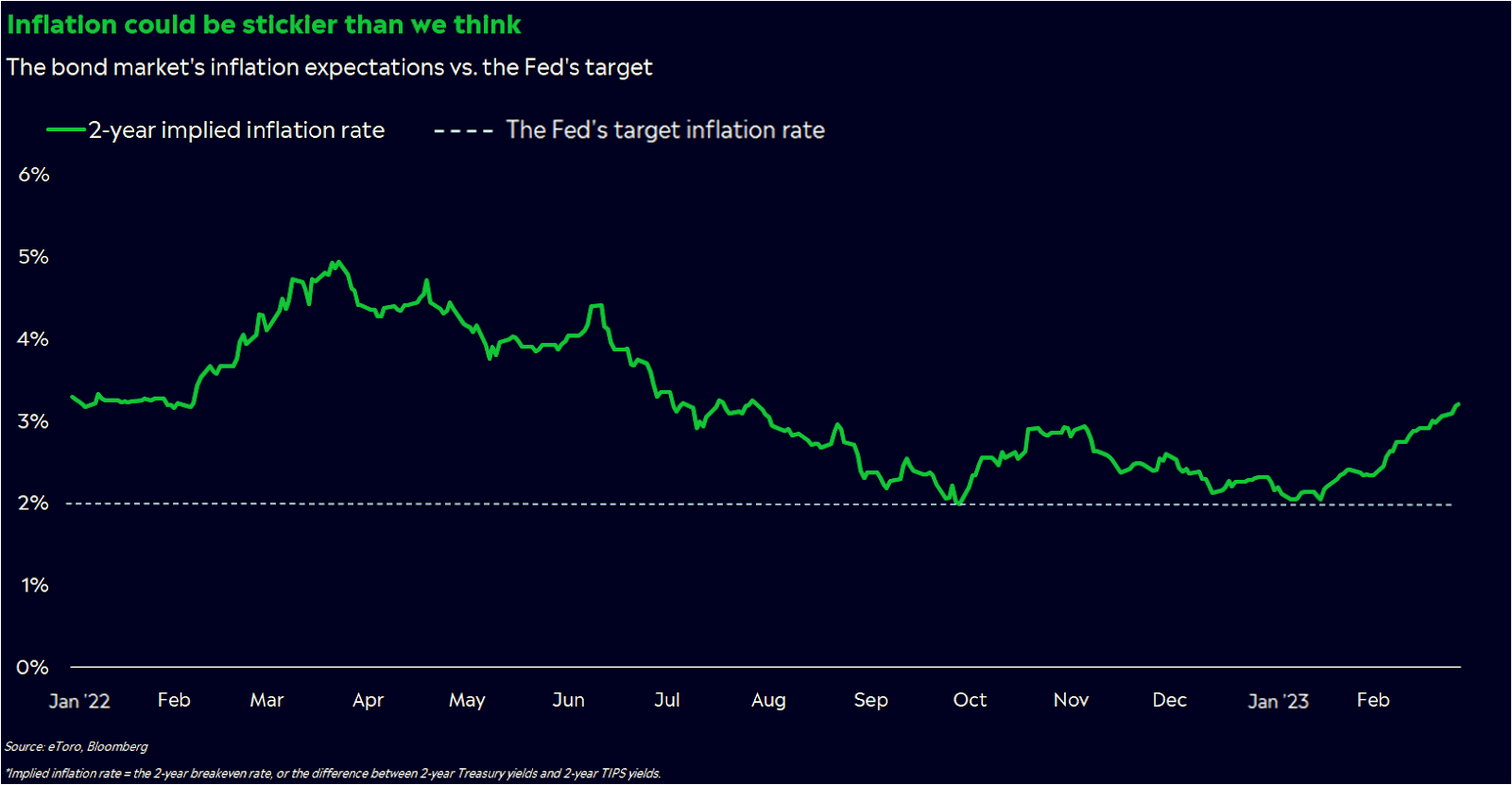

Inflation expectations are rising

Inflation is still fiery hot, with prices growing more than 6% year over year, despite a year of Fed rate hikes.

Up until now, the Fed has had one powerful tool on its side: investors’ belief that it could get inflation back down to a pre-COVID level of 2%. Even as year-over-year Consumer Price Index growth accelerated to 9%, market-implied inflation expectations from two to five years moved gradually lower. This has been a powerful advantage for Jay Powell, and it’s a key difference between now and the 1970s stagflation crisis.

Today, though, that advantage seems to be eroding. In February, two-year implied inflation rates rose from 2.3% to 3.2%, indicating that investors think the Fed won’t reach its 2% target before 2025.

Five-year implied inflation rates edged up as well, a sign the market is losing faith in the Fed’s ability to control long-term inflation.

This isn’t what you want to see when the Fed is actively trying to get inflation down. If people expect inflation to stay high, they could change their spending habits and pay demands to match that, which could push inflation up more. It’s a vicious cycle that could sow distrust in the financial system, and it’s ultimately what the Fed is trying to avoid in its rate-hike journey.

Before you freak out, this probably isn’t another case of Weimar Republic-like hyperinflation. Hyperinflation isn’t just an expensive cup of coffee — it’s when inflation rises more than 50% in a month — and it often coincides with a currency collapse. We may even be in better shape than the 1970s, when CPI grew an average of 7% year over year.

Why persistently high inflation can be dangerous

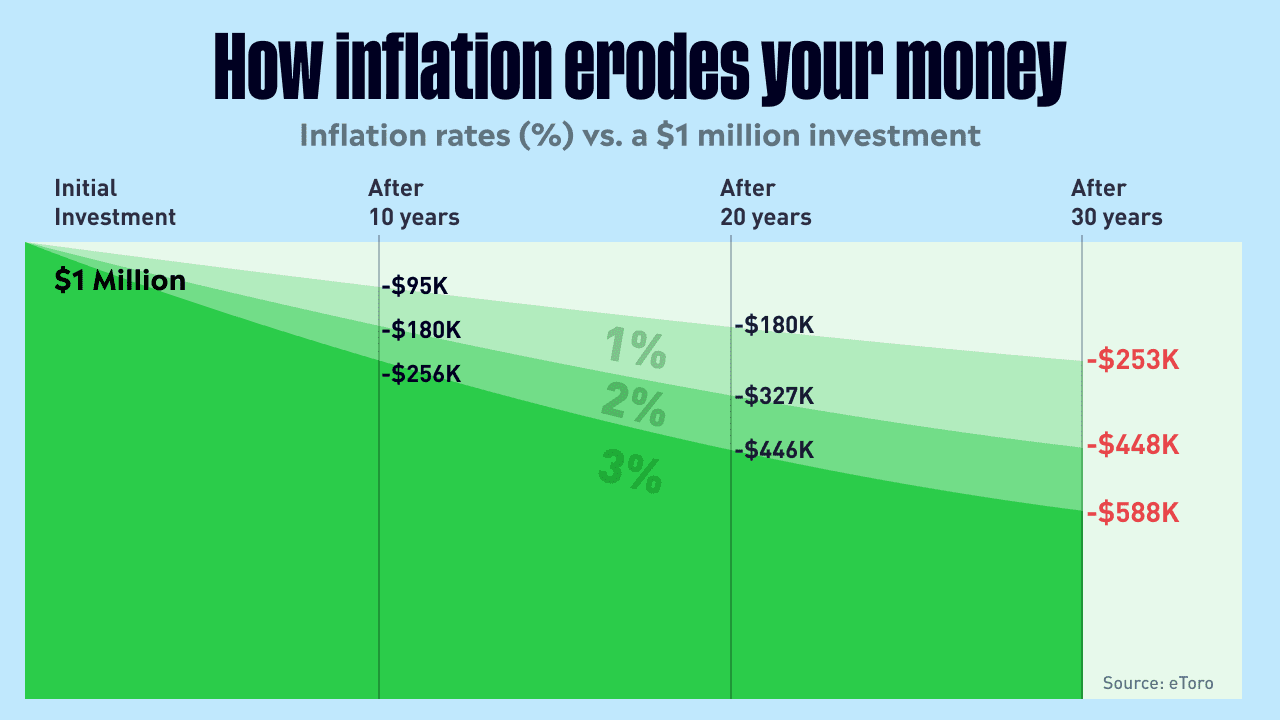

Even if inflation doesn’t spiral out of control, it can be dangerous if left unchecked.

Why? Because inflation erodes the value of money over time. In a healthy economy, you should expect some inflation. But when prices rise faster than your paycheck — as we’ve collectively experienced over the past 21 months — you could find yourself at the grocery store wondering why your budget doesn’t stretch as far as it did last month.

It’s all because of the time value of money.

Imagine you had $1 million in your savings account earning no interest whatsoever. That $1 million won’t be worth $1 million in the future if inflation is in the picture. If prices rise 3% in a year, that $1 million would effectively be worth $970,000 a year later, and inflation’s impact can snowball as time goes on. At 6% inflation, your $1 million would lose half its value in just 12 years.

But it’s not just about the math.

High inflation can warp our thoughts around money and risk.

When prices are rising quickly, many of us consciously — or subconsciously — make different choices. We revisit our budgets, cut our discretionary spending, and make personal sacrifices to make sure we can afford what we need. These small changes amount to big decisions, like renting instead of buying a house, choosing one job over another, or moving cities for better opportunities. Suddenly, your life looks dramatically different. And collectively, the economy suffers from a “paradox of thrift” — a shift toward savings that ultimately drags on growth.

Inflation also adds another element of uncertainty. As humans, we naturally gravitate towards predictability and shy away from the unknown. So when prices aren’t as predictable over months and years, we start to operate in weeks and days.

In an investing sense, inflation incentivizes us to consider short-term, fixed income over long-term, variable growth. As you can imagine, that could be a tricky prospect for a long-term investor, when it’s typically advantageous to lean on growth over income. You may be more tempted to act cautious and build up your cash reserves too much, even though you could afford to take more risks.

On a more disheartening note, high inflation can also drive a wedge through society. A Fed Bank of Dallas study published earlier this year showed that households in lower income brackets tended to be more stressed over inflation than higher income households. It makes sense — food and rent prices are rising especially fast, and they comprise a greater percentage of lower income budgets.

This is the most damaging consequence of persistent inflation. We’re living in the days of income inequality and instant gratification, and inflation threatens to amplify these trends even more. And like Jay Powell has said before, without price stability, the economy doesn’t work for anyone.

Persistent inflation could be a game-changer for many different aspects of our money and our lives, and it’s one of the biggest risks we’re watching on the market’s horizon.

*Data sourced through Bloomberg. Can be made available upon request.