This week, 2-year yields traded above 10-year yields for a few minutes.

For a brief moment in time, Treasury investors were faced with the choice to get paid a lower interest rate to lock their money up for eight extra years. In Wall Street speak, the yield curve inverted.

It breaks down like this…

Typically, a 10-year bond yields more than a two-year note because you naturally assume more risk if you loan your money out for longer periods of time. But when two-year notes yield more than 10-year bonds, investors essentially want a higher payment for lending their money out over a shorter period of time. Are we in the Bizarro world?

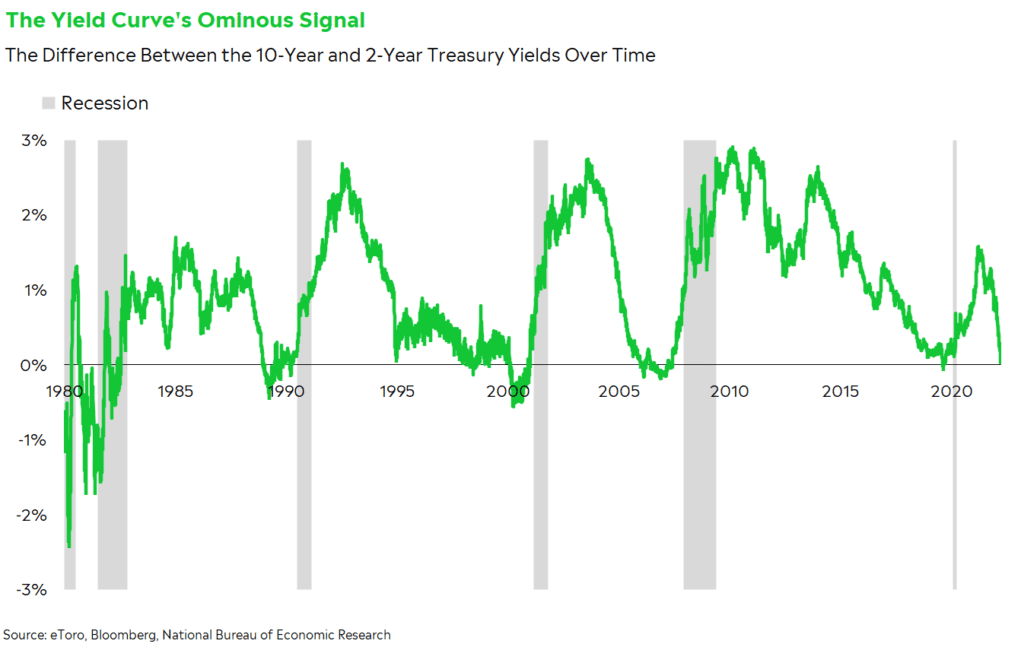

The yield curve’s shenanigans have ignited a conversation around if the bond market is sniffing out something ominous on the horizon. Investing veterans have pointed out that the spread between the 2-year and 10-year yields typically falls negative before recessions.

But it may be a false alarm.

The yield curve

At first glance, the yield curve’s shape seems like a niche metric that only nerdy bond traders should care about. But the yield curve can tell us a lot about what investors expect in the future. It can show how comfortable both borrowers and lenders are with different points in the future.

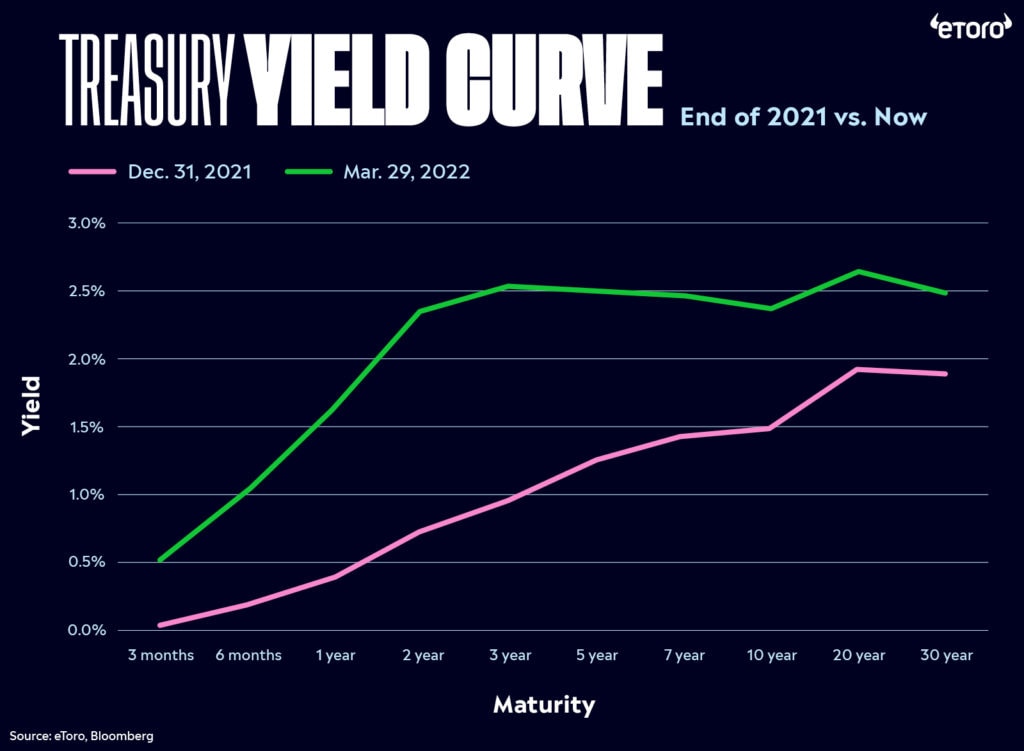

These days, people are on high alert for any signs of incoming trouble. So when the spread between the 2-year yield (a gauge of future Fed moves) and the 10-year yield (a proxy for the economic outlook) started barreling toward zero, the market paid attention.

Now, with inversion upon us, it looks like the Fed may be at risk of hiking beyond what the economy can handle. And the 2-year/10-year spread is seen as a classic recession signal. In the past six economic cycles, the economy has entered a recession an average of 18 months after the spread between the 2-year and 10-year yields first fell negative.

The context

For some investors, that track record is tough to overlook. But context matters here, especially when you’re jumping to such a dramatic conclusion.

Yes, the 2-year/10-year yield spread is close to zero, but other parts of the yield curve look seemingly normal. Take the 3-month/10-year yield spread, which has also fallen negative shortly before each of the past six recessions. It’s currently sitting at 1.8%, showing that the market isn’t necessarily worried about where the economy could be three months from now.

Plus, calling the 10-year yield a true economic proxy is a bit of a stretch. These days, long-term Treasuries aren’t simply just people lending money to the government for a payout. They’re a hideout for international investors plagued by negative interest rates and geopolitical situations overseas. They’re also a favorite of the baby boomer generation as they increasingly approach retirement. Even the Fed owns about $6 trillion of outstanding Treasuries after its COVID crisis bond-buying. It’s hard to trust the signal of a market with so many forced buyers.

No recession indicator is foolproof. But in these days of new-age market support and demographic forces, we may need to retire our idea of the yield curve inversion as a red flag.

The risks

The yield curve alone may be more noise than signal, but it’s another notch in the economy’s risks column. Americans are already unusually nervous about the future. According to the University of Michigan’s consumer sentiment survey, consumers haven’t felt this bleak about their finances in at least four decades. Rates on financial products like mortgages are rising, providing more incentive to save instead of spend and invest. Headlines about yield curve inversions and $4 gas don’t exactly inspire confidence.

For what it’s worth, US companies are preparing for a spendy summer. Businesses are still hiring at a rapid pace and building up their inventories because they expect demand to continue. And rates on company debt offerings are surprisingly stable, despite all the movement in the Treasury market.

The economy looks decent for now, but it’ll be key to watch if — and how quickly — Americans act on their words. Consumer spending is the most powerful force in the economy. If consumers lose faith, a recession may be more likely.

The vibes

You’re justified in feeling a bit paranoid about the yield curve. But don’t fall into the bear trap of trying to call a recession based on one data point. History has shown that recessions are quick and (mostly) unpredictable – remember the COVID economic crisis? But most of the time, the US economy is expanding. The yield curve may be sending cautious vibes, but don’t overlook the good vibes elsewhere.

Instead of focusing on when a recession will happen, it may be worth giving up the guessing game and just preparing for the unexpected regardless of yields. Think about which sectors tend to shine in a low-growth environment, and tailor your individual investments to ensure your portfolio is battle-proof if a downturn does happen. And if you’re still worried about the future, it never hurts to stash some extra cash.

*Data sourced through Bloomberg. Can be made available upon request.